CML paper summary - November 2025

How I manage chronic myeloid leukemia during pregnancy

Abruzzese E et al. Blood, August 2025

Link to full paper: https://ashpublications.org/blood/article-abstract/doi/10.1182/blood.2024026513/546477/How-I-Manage-Chronic-Myeloid-Leukemia-During?redirectedFrom=fulltext

Summary

This comprehensive review provides practical, scenario-based guidance for managing chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) during pregnancy. As tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) are teratogenic – particularly during organogenesis – they must be discontinued immediately when pregnancy is confirmed. Interferon-α (IFN-α) is the safest cytoreductive option throughout pregnancy, while imatinib or nilotinib may be cautiously considered after 16 weeks in selected situations due to limited placental transfer. Management decisions depend on disease phase, depth of molecular response at conception, gestational age, molecular kinetics, and patient values. Seven real-world cases illustrate best practices, emphasising shared decision-making, frequent molecular monitoring, and individualised treatment strategies. When carefully managed, maternal and fetal outcomes can be favourable.

Key points for clinicians

- TKIs should be stopped at the first positive pregnancy test to avoid teratogenic exposure during weeks 5–10.

- IFN-α is the preferred therapy at any gestational age; hydroxyurea may be used only briefly for uncontrolled hyperleukocytosis if leukapheresis is unavailable.

- Imatinib and nilotinib can be considered after 16 weeks; dasatinib must be avoided due to high placental crossing and fetal toxicity.

- Treatment strategy depends heavily on initial response status: women in stable deep molecular response (DMR) have the best chance of remaining untreated during pregnancy.

- Rapid rises in BCR::ABL1 transcripts (>1–10%) or loss of complete hematologic remission (CHR) warrant reinitiating therapy.

- Breastfeeding is not recommended with TKIs; could be considered if on IFN.

Introduction

The advent of TKIs has transformed CML into a chronic, manageable disease, expanding expectations around fertility and family planning. As many women of childbearing age now live long-term with CML, oncologists increasingly face the challenge of managing pregnancy safely. TKIs are highly effective but largely contraindicated in early pregnancy due to teratogenicity; thus, pregnancy requires a balance between maternal disease control and fetal protection.

Two major clinical situations arise:

- CML newly diagnosed during pregnancy, often requiring urgent cytoreduction without TKIs.

- Pregnancy occurring during TKI therapy, where treatment interruption, monitoring, and sometimes re-initiation are critical.

This article provides detailed therapeutic guidance - including drug safety profiles, monitoring recommendations, and case-based insights - to support hematologists in optimising outcomes for both mother and child.

Methods

This is a narrative, expert-driven “How I manage” review using:

- Seven real clinical cases illustrating typical and complex CML and pregnancy scenarios.

- Extensive review of literature, registry data, pharmacokinetic studies, and embryology to guide safety assessments and therapeutic decisions.

- Summaries of drug mechanisms and placental transfer data, including Hydroxyurea, IFN-α, and all approved TKIs.

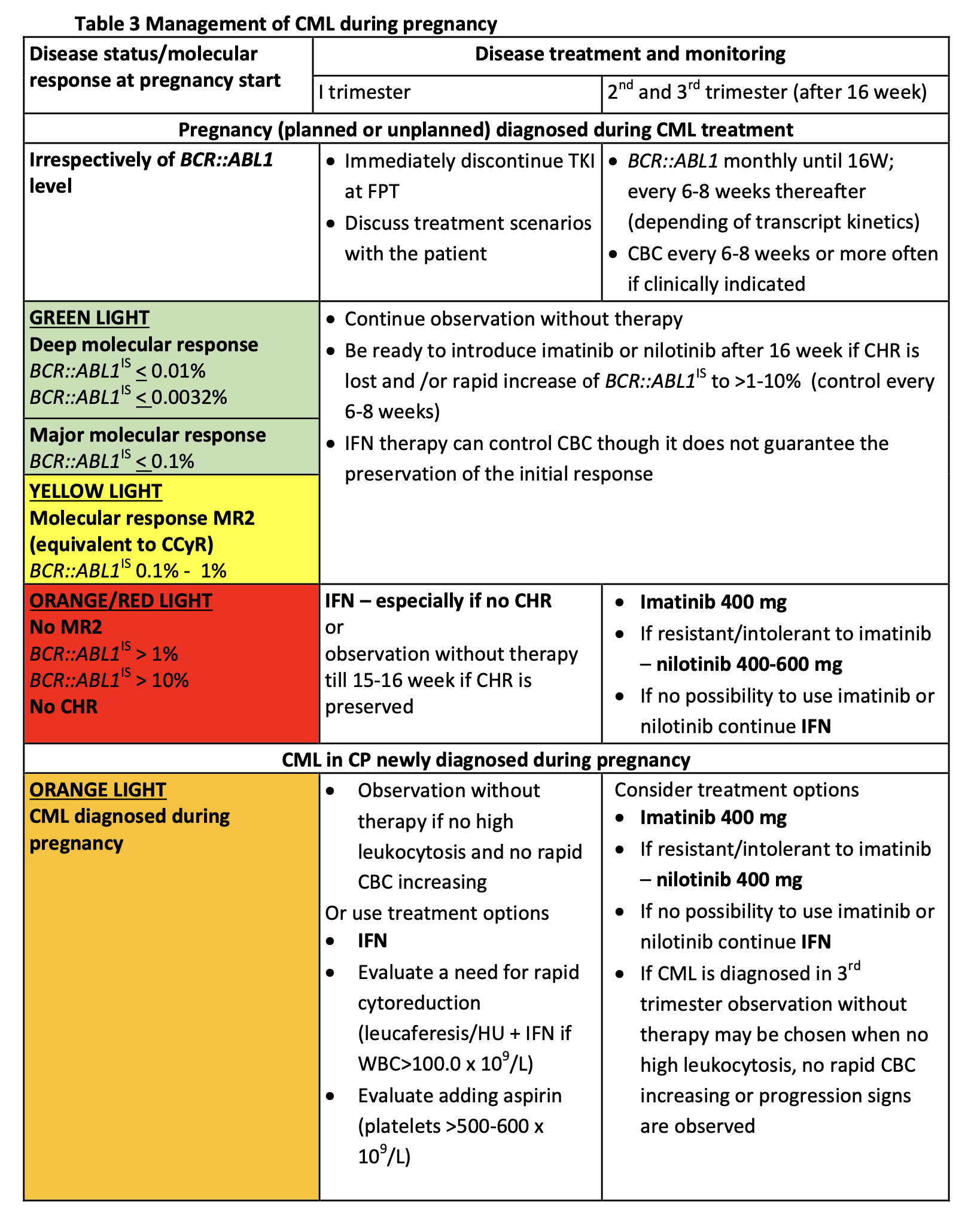

- A management algorithm (see table) for first, second, and third trimesters depending on BCR::ABL1 IS levels, remission status, gestational age, and cytopenias.

The review’s strength lies in translating guidelines, clinical evidence, and pharmacologic principles into practical recommendations across diverse clinical circumstances.

This research was originally published in Blood. Abruzzese E et al. How I manage chronic myeloid leukemia during pregnancy.

Blood 2025 Aug 4:blood.2024026513. doi: 10.1182/blood.2024026513. © by the American Society of Hematology.

Key findings

Drug safety profiles during pregnancy

- Interferon-α (IFN-α) – safest agent

- Does not cross the placenta; long safety record.

- Effective for complete hematologic response (CHR) and modest molecular control.

- Preferred first-line option in all trimesters.

- Tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs)

- First trimester (weeks 5–10): all TKIs contraindicated due to teratogenicity.

- Second–third trimester: Imatinib or nilotinib may be considered if BCR::ABL1 rises or CHR is lost.

- Dasatinib: must be avoided – freely crosses placenta; linked to fetal hydrops, malformations, IUFD.

- Bosutinib: limited data but theoretically high placental transfer; discontinue during pregnancy.

- Ponatinib and asciminib: insufficient safety data; avoid.

Maternal disease management principles

- Immediate steps when pregnancy is confirmed:

- Stop TKIs at the first positive pregnancy test (typically week 3–4) - exposure before this period is unlikely to cause anomalies.

- Begin intensified molecular and hematologic monitoring.

- Monitoring frequency:

- Monthly BCR::ABL1 until week 16, then every 6–8 weeks depending on kinetics.

- CBC every 6–8 weeks or more if cytoses rise.

- When to initiate or reinitiate therapy:

- Initiate IFN-α if:

- No CHR

- Rapid kinetics in newly diagnosed CML

- Rising BCR::ABL1 (e.g., >1–10%)

- Restart imatinib/nilotinib (after 16 weeks) if:

- Rapid transcript rise

- CHR threatened or lost

- IFN-α insufficient

Fetal considerations

- Critical teratogenic window: weeks 5–10 (organogenesis).

- After week 16, placental barrier reduces drug transfer; malformation risk is lower.

- Limited data but reassuring long-term developmental outcomes for children exposed to chemotherapy/TKIs in utero (mostly late exposure).

Breastfeeding

- Not recommended with any TKI (drug transferred into breast milk).

- Allowed with IFN-α or off-therapy.

- Breastfeeding must be weighed against need for rapid TKI resumption postpartum.

Case-based practical insights

The seven cases cover:

- Case #1: Newly diagnosed CML in early pregnancy:

- IFN-α safely controlled hyperleukocytosis

- Demonstrates feasibility of avoiding TKIs entirely until delivery if CHR is achieved.

- Case #2: Newly diagnosed in second trimester:

- Hematologic control may improve spontaneously due to plasma volume expansion; treatment may be deferred.

- Case #3: Early pregnancy during TKI therapy (not yet TFR candidate):

- Loss of MR3 or rapid BCR::ABL1 increase requires restarting imatinib.

- Case #4: Pregnancy in patient with prior resistance requiring ponatinib:

- Achieving DMR with ponatinib + IFN combination enabled safe TKI cessation at conception.

- Case #5: Planned pregnancy with stable MMR but not TFR candidate:

- Nilotinib restarted in late second trimester after molecular relapse; no placental transfer detected in cord blood.

- Cases #6 and #7: TFR candidates with rising transcripts during pregnancy:

- IFN-α can bridge pregnancy until postpartum even when BCR::ABL1 rises, avoiding TKIs during organogenesis.

Conclusions

Managing CML during pregnancy requires a multidisciplinary, individualised plan that prioritises fetal safety while ensuring maternal disease control. Early discontinuation of TKIs, frequent molecular monitoring, and timely initiation of IFN-α are central strategies. Imatinib or nilotinib may be reintroduced after 16 weeks when clinically justified, but dasatinib and newer agents (bosutinib, ponatinib, asciminib) should be avoided.

Although no single approach fits all cases, successful outcomes are achievable with shared decision-making, education, careful assessment of disease kinetics, and flexible treatment adjustments. Real-world cases highlight that – even in challenging scenarios - healthy pregnancies and long-term maternal remission are realistic goals when evidence-based principles are applied.